Contemporary Christian Music (CCM) hits 50 years old this winter. This 4-part series tells its story and is an expanded version of the feature Christianity Magazine published in Dec 2019.

The ‘sixties were an exciting time to grow up. Everything was changing and there was brightness everywhere. Our parents’ photos were black and white, but ours were in colour; their music felt worn out and grey, but ours was psychedelic; they wore grey and brown clothes, but ours were in vivid blues, oranges and purples.

‘Generation Gap’ was a phrase bandied about, because our parents’ generation struggled to cope with the speed of this change and the fundamental shift in values. They had lived through the war, with its frugality and sacrifice, while we were the peace and love generation, who only knew the boom years.

Humans were hurtling into space and we looked not to the past, but to the boundless possibilities of the future. Call me pretentious, but for me, comics like The Dandy were passé, and I looked forward to each new edition of TV21, full of Gerry Anderson creations – Thunderbirds, Captain Scarlet and Stingray (although I did get sensible and start reading The Beano in my teens).

Music was a core part of this cultural revolution. Not only were The Beatles and The Rolling Stones creating new music, but they were influencing lifestyle by their confrontational disregard for the norms of the day, their drug use and their wholehearted devotion to “the permissive society.”

But while teenagers did not look the same in 1969 as in 1959, churches did. However psychedelically they dressed from Monday to Saturday, youths still wore suits to church (and no one working for a church organisation would dare to be photographed without a tie). The hymns-and-organ music didn’t change much, either.

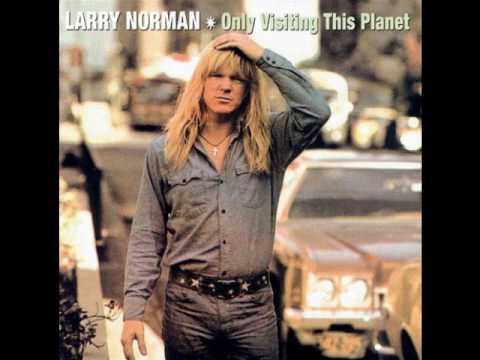

There must have been many sermons denouncing long-haired hippies, seen as lazy louts who congregated in their thousands at the Isle of Wight Festival, using locals’ well-manicured gardens as urinals. But God was on the move and change came via a wholly unexpected source. A denim-clad hippie with shoulder-length blonde hair was the pioneer who gave young Christians their own music; something that could stand alongside the secular styles that gave them their identity, while expressing the new life inside them. His name was Larry Norman.

Commentators generally agree that Norman’s “Upon This Rock” album, released fifty years ago this winter, began what came to be known as Contemporary Christian Music (CCM). He had already seen chart success with his band People!, but was peeved when his label blocked the album title “We Need a Whole Lot More of Jesus and a Lot Less Rock & Roll,” so he left and went solo.

With his signature “One way” upwards-pointed finger gesture, denoting Jesus as the only way to salvation, he became the poster boy for new Christian music.

His landmark album “Only Visiting this Planet” sealed his place in history. In 2013, it was one of 25 sound recordings inducted into America’s Library of Congress National Recording Registry, which preserves “cultural, artistic and/or historical treasures, representing the richness and diversity of the American soundscape.” The library rightly called the album “the key work in the early history of Christian rock.”

Notably, the album’s approach still works as a template of what Christian music should be: speaking to the world around with creativity and skill, critiquing contemporary society, making a stand for Christian values and pointing the way to Jesus, all from within that culture, so making it authentic.

But its line “gonorrhoea on Valentines Day (VD)” wasn’t too popular with Christian bookshops and he was often quoted as being “too religious for rock and roll stores, and too rock and roll for the Church.”

Early tensions

Mixing faith and the new music was risky. On this side of the pond, Cliff Richard remembered reading about, “Christian fundamentalist preachers in America, burning rock and roll records – and thinking, ‘Oh, my goodness, that’s me!’ And, while it did not get that bad in the UK, he told me, “I couldn’t help but be affected by that; there was a feeling that rock and roll and church didn’t go together.” Sir Cliff had come to faith, but was not releasing ‘gospel’ material.

The black church had had similar issues with its ‘Saturday night, Sunday morning’ split-personality, but musically, it has always been in the vanguard of developments, with blues and gospel being part of the mix that produced rock & roll.

In 1969 Edwin Hawkins Singers had an international hit with “Oh, Happy Day” and in 1972 Aretha Franklin recorded “Amazing Grace” – her best-selling album and the best-selling live gospel album of all time. Gospel music has consistently continued to be in demand for its soulful verve. As the universal acclaim heaped upon this year’s release of the documentary that accompanied Franklin’s album testifies, black gospel has never had the credibility issues that have regularly stalked CCM.

In England, probably completely out of view of American commentators, several English bands were already tentatively blazing a trail. The Pilgrims and the Hendrix-inspired Out of Darkness were notable – and very different – names among several who prepared the ground for the explosion that happened in the ’70s.

A rare example of a track hitting the charts and residing on youth groups’ songbooks at more or less the same time was Christian folk trio Parchment’s 1972 hit “Light Up the Fire,”which was the theme song to the Nationwide Festival of Light (a Christian movement aimed at reducing “moral pollution”). Youth magazine Buzz noted that Radio One DJ Tony Blackburn said he wouldn’t play it, even if it got to Number One – so there was tension on both sides of the cultural divide.

Singer songwriter Bryn Haworth was on the original roster of the groundbreaking Island record label, and was soon to gain a reputation as England’s leading slide guitarist. After strangely experiencing someone on stage with him one night, whom no one else saw, and later finding himself in a revival tent, thinking it was a circus, he came to faith and his music has reflected that faith ever since.

Remembering the struggle in his early years, he told me about coming to terms with the cultural problems of the time, “After a year of churchgoing, we thought, ‘We can’t do this, it’s too alien a culture’ and were about to give up. Garth Hewitt, a fellow Christian musician, who was keeping a pastoral eye on us, recognised we were struggling and invited along to the Albert Hall to see Larry Norman. We went along reluctantly, but loved it, and were so encouraged. We thought, ‘Well, if he can follow Jesus and be himself, then so can we’.

“When my wife, Sally and I became followers of Jesus back in 1974, it was hard to find Christian music that we liked. It was generally different to the style of music that I wrote. But then we bought Andre Crouch & The Disciples’ Live at Carnegie Hall album and loved it! This really freed me to express Jesus in my own musical style.”

Front runners

Haworth was not the only one searching out good faith-based material. So many young Christians wanted to hear music that expressed their own faith in the style of their other records, whether pop, folk or rock, that when a good band came along that proudly featured their faith, they were assured grass roots support.

In the UK, After the Fire were brand leaders, and so good that they headlined the Greenbelt Festival on both the opening and closing nights in 1975. They composed music that had spiritual depth, genuine prog vibe, memorable tunes and real hooks. With a dedicated following and strong material, they were on the fringes of a record deal for some while, but it took so long that they had to transform their sound to New Wave in the meantime.

As a consequence, the prog material that gained them their cult status was ditched and to keep a record of it, the band had to self-produce the Signs of Change album. Unfortunately, it suffered from a woody drum sound and failed to catch the power of their shows (or front man Andy Piercy’s stage puppet movements during the “Song of the Marionette”).

Also gaining a following amongst those in the know was Gravytrain, who shared a lot of musical ground with Jethro Tull (a mix of riffy rock, extended guitar solos and flute). Their genial frontman Norman Barratt had come to faith in 1969 and let that inform all his lyrics, which had big elements of storytelling and social responsibility, such as his account of the Tolpuddle Martyrs.

In America, it was groups like Petra and Resurrection Band who first played quality accessible rock with a prog twinge and likewise developed a following.

But none of these had the longevity of guitarist Phil Keaggy. Starting off in rock trio Glass Harp, he soon showed a proclivity for working solo and, after one fine release with his own band, has created a string of some 50 albums varying from electric blues rock to acoustic Spanish guitar. Along the way he has collected awards and nominations for his skills, including from major secular guitar magazines. Notably, he was the first to release instrumental albums in the CCM arena – causing consternation to those who thought that only lyrics could justify something being Christian.

Having started to play the ukulele at age three, and becoming youngest person ever to sign with ASCAP (the American Society of Composers, Authors and Publishers) at eleven, a young Keith Green was named in Time magazine as Decca Records’ “prepubescent dreamboat”. When he and his wife Melody came to faith in 1975, his work became so spiritually charged – hear his 1978 album No Compromise – that some called him a prophet.

After agreeing a release from his Sparrow Records contract the next year, he refused to charge for either albums or shows, asking people to give what they could afford (beating Radiohead by decades). Privately financing his next album, the less fiery and more pastoral So You Wanna Go Back to Egypt, over a third of them were given away.

Guesting on harmonica on that album was Bob Dylan, whose conversion was a dramatic event. For such a counter-cultural icon to espouse what many saw as the institution of Christianity was the biggest shock to his fans since he turned electric at Newport in 1965, and probably gave them an even greater sense of betrayal.

Several members of Dylan’s mid-decade backing band for the Rolling Thunder Revue tour had come to faith and were associated with the new Vineyard Fellowship. In 1978, after someone had thrown a cross onto the stage, which he picked up and kept, Dylan had an experience of Christ in a hotel room and later claimed, “There was a presence in the room that couldn’t have been anybody but Jesus … Jesus put his hand on me. It was a physical thing. I felt it all over me.”

The impact on his music was considerable and he released a trio of specifically Christian albums. Slow Train Coming was one of his best-sounding albums ever, graced by Muscle Shoals players and Mark Knopfler’s distinctive guitar licks; but it was a blunt, apocalyptic work that reflected the power of his conversion (as well as Hal Lindsey’s book The Late Great Planet Earth). By contrast, Saved burned with a joyous gospel vibe and Shot of Love had a looser, almost shambolic feel and let faith drive the album, rather than frame its borders. Within a year of the last being released, three of his colleagues were dead. One was Keith Green, who died in a plane accident.

Dylan was not the first big name to make an impact with quality faith music. Arguably the first musician to bring absolute musical excellence after Larry Norman was session keyboard player Michael Omartian, a regular with acts like Steely Dan, a collective of musicians’ musicians. His début release White Horse featured fellow session players like Larry Carlton and Abraham Laboriel. The songs and sound were so good that the album still has power today. Omartian went on to become a record-breaking producer for acts like Rod Stewart, Donna Summer and Christopher Cross, having number one albums in three consecutive decades.

As the ‘seventies ended, Christian music just began to hit its peak, with major names putting out music, record labels falling over themselves to set up their own imprints and sales beating genres like jazz.

Details of that in Part Two.

This article is a director’s cut of the shorter piece published in Christianity Magazine in December 2019

Whilst it’s nice to be reminded of the emergence of early contemporary Christian music, it is sad, that like so many, you see Larry Norman as the pioneer. Don’t get me wrong, he was the first Christian rock star, with an attitude to match. Hugely influential, no doubt. But the real pioneers were actually British youth, playing pop and Beatle style in the 60s. A Christian band called ‘Out of Darkness’ were playing the kind of guitar driven rock music, in the late 60s, when a lot of what Norman did was still folk style (see ‘Only Visiting this Planet’). Because so much of contemporary Christian music is derived form the USA, I wonder we easily embrace their perspective which sees Norman as the starting point. He wasn’t. For a book about the British (and the true pioneers) see my book ‘The Sounds of the sixties and the church’, available on Amazon. Stephen Wright

Hello Stephen,

Thanks very much for this. I thoroughly agree that the ‘start date’ for CCM as Upon This Rock’s release is probably due to an American perspective amongst commentators.

I also agree that Out of Darkness were key in the British scene in the late ‘sixties. I once saw their guitarst Wray Powell play a very Hendrix-inspired set at Greenbelt (he looked the part, too) and tried to make contact with their Tony Goodman during the (eleven years) of research for this piece, via Kingsway Records (no reply) as his son recorded for them (as I’m sure you know) as part of the superb band Note for a Child.

I think my attempts ended largely because you can expand and expand this – for example, one source, Mark Allen Powell’s Encyclopedia of CCM was 1088 pages’ worth of dense entries even back in 2001! It was initially proposed to Christianity Magazine in roughly this 4-part form a decade ago and re-proposed in a condensed 2-part format last year. It eventually became just a 3,000 word commission. So at this point, there was no room for mention of earlier influences.

So had it been longer, OOD would almost certainly have had a mention. Regeneration Rock, from where After the Fire’s original bassist Robin Childs came, could also have been covered. But where do I draw the line(!)? I have already had to omit so much potential content. That’s also why I have been happy to go with the Larry Norman date, as you have to pick a point somewhere, if you’re celebrating an anniversary. I think another reason for 1969 being a valid date to work from is that his album caused a significant sea change. Few pioneers come completely out of the blue, and while bands like OOD were highly significant torchbearers, Larry got the floodgates opening.

I’m very happy for your book to be listed here for anyone looking further and thanks again for your very valid comments.

Best wishes, Derek

Thanks Derek, I appreciate your kind and considered reply.

I also appreciate that it is difficult to know where to start and I can see that Larry Norman is as good as any. His style and way with words certainly set him apart from anything that had gone before, in Christian terms at least.

On the other hand, there is a British contribution that people ought to be aware of. My book began as an attempt to argue that not all Christians were against the new styles of music that emerged in the 60s and 70s, contrary to what was often thought. During my research I discovered an enormous wave of creativity as Christians responded to beat music and the Beatles sound. As Christian music evolved and became more professional, I sense that these beginnings were often dismissed and discounted as amateurish and lacking in quality. No doubt, this may have been true, but there were some like the Crossbeats and Pilgrims for example, for whom, it was most certainly not. These are the forgotten pioneers of Christian music and a work like Powell’s Encyclopedia entirely overlooks them, largely I guess, because as an American, he was unaware. As Brits we ought to be aware and to know where truly, it all began.